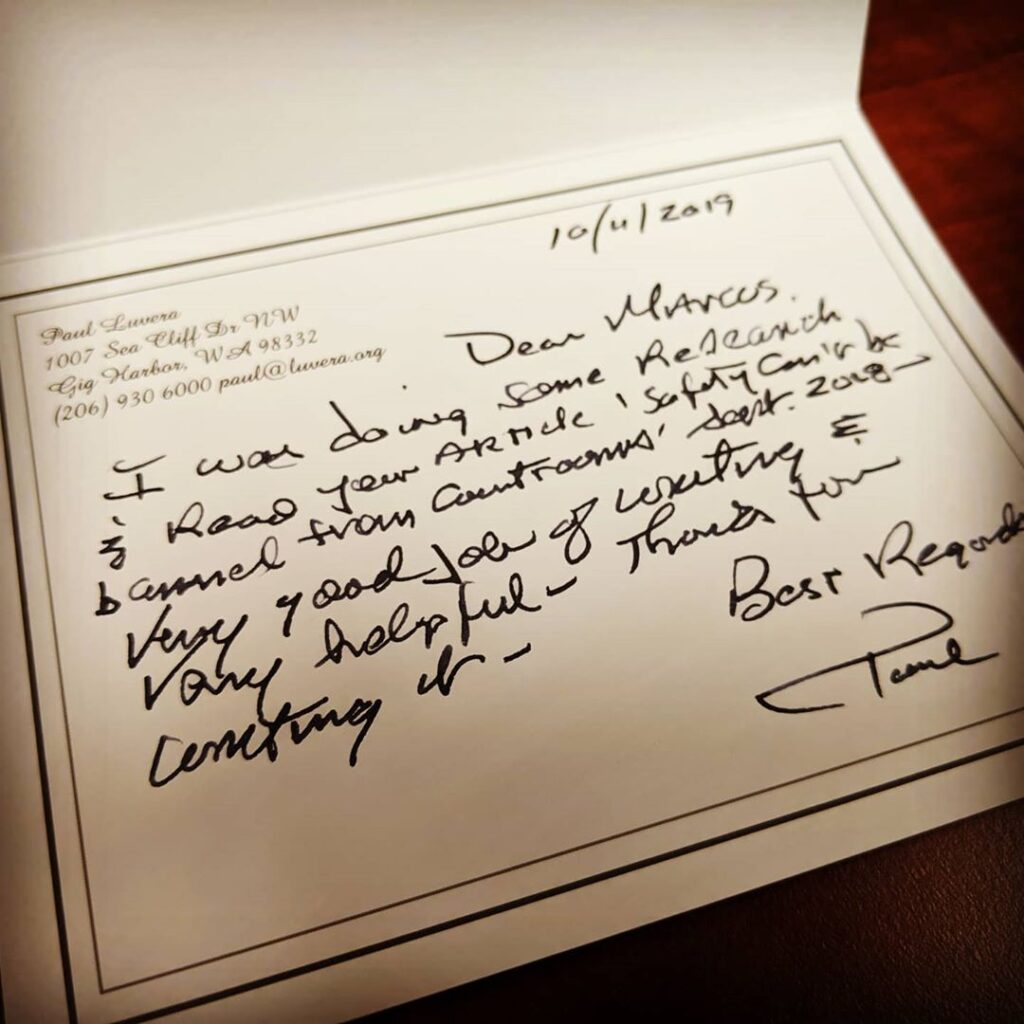

It was an honor to be published in Trial News, by the Washington Association for Justice. It was also especially sweet to receive a personal note of thanks for writing the article from Paul Luvera, a Washington State trial attorney I have long followed and highly respect. Mr. Luvera is one of the most respected trial attorneys of our time, and talked about the value of the article on his own blog in October 2019.

The article is republished below.

Safety Cannot Be Banned from Courtrooms

Minutes before opening statements were to begin, the judge commented that he thought the words “safety rule” might be inappropriate, inviting objection. To the astonishment of no one, defense counsel rose from his chair to contend that introduction of the term “safety rules” was unduly prejudicial; the jurors were so fragile that, based upon the presentation of safety rules, the jury would become paralyzed with fear and want to act for the foreseeable interests of their community.

It was my first trial since partnering with my father in his Spokane personal injury practice. A man in black robes admonished that “safety rules” were not to be published or argued in the courtroom. Later, he would exclude ASTM safety standards from being admitted into evidence, preclude experts from opining on what constitutes “reasonable care,” and then permit the defense to argue that no duty exists because a legislative body had not adopted a regulation that applied to the circumstances of the case. “Is this how the civil justice system is supposed to work?” I wondered. I hope every EAGLE reading this gives their newest hire a confident “No.” Here’s why:

“Over a century ago, the United States Supreme Court declared the “great principle that every community has a right to provide for the safety of its people… Salus populiest suprema lex [Let the safety of the people be the supreme law] is a maxim always true in all nations, and must be acted upon by all civilized, as well as all uncivilized, nations.”

At the core of their societal purpose, trial lawyers across Washington serve as officers of the court, to safeguard their local community’s right to prudence and safety.”

Due process guarantees the right to stand up for one’s rights, to have one’s day in court, and to exercise the wide latitude to persuade. Plaintiffs have the right— in fact, the burden— of showing evidence of “foreseeable risk and threatened danger.” An order precluding presentation of a safety rule as evidence of foreseeable risk or threatened danger, as evidence of industry or community standards, as evidence of a safer alternative, or as a basis of expert testimony, is contrary to Washington law.

A motion in limine is “a pretrial request that certain inadmissible evidence not be referred to or offered at trial.” Motions in limine must “describe the evidence which is sought to be excluded with sufficient specificity to enable the trial court to determine that it is clearly inadmissible.” A blanket order banning a trial strategy or precluding plaintiff’s counsel and witnesses from using specific words or phrases is not based on certain inadmissible evidence, and it infringes upon a plaintiff’s constitutional right to fully support and argue their theory of the case.

Safety rules are embedded throughout Washington law. Potential safety measures are proper for the jury to consider as standard of care evidence. The Washington Pattern Instructions instruct the jury that the “duty to exercise ordinary care” exists to protect others’ “safety.” The jury must evaluate whether the defendant exercised reasonable care under the circumstances, including whether the defendant considered the foreseeability of harm, the gravity of their risks, the safer alternatives available, and the community or industry standards that are expected. The jury may “consider logic, common sense, justice, policy, and precedent, as applied to the facts of the case, when determining whether a defendant owes a duty in tort. We have long applied these factors when defining ‘duty,’ and they can be traced back for more than 100 years.”

Safety standards are indisputably the underlying concept of the “reasonable person.” “Our legal system has entrusted negligence questions to jurors, inciting them to apply community standards.” The words “reasonable person” denote “a personification of a community ideal of reasonable behavior, determined by the collective social judgment.” By its very definition, “negligence is a departure from a standard of conduct demanded by the community for the protection of others against unreasonable risk. The standard which the community demands.” The jury must “look to a community standard rather than an individual one.” “Conduct that falls below a legal standard established for the protection of others against unreasonable risk amounts to negligence.”

Safety standards need not be adopted by a legislative body. Tort law is all-encompassing and designed to define the obligations that individuals and entities owe each other in society in the absence of regulation. Every “person has a duty to prevent unreasonable risk of harm to others from his or her own actions.” Defense counsel may attempt to undermine the introduction of safety rules with arguments akin to “no specific law has been adopted that says the defendant’s conduct needs to meet this standard.” This argument, whether made to the trial judge or the jury, improperly shifts the burden of proof by espousing a belief that negligence per se is required to hold the defendant accountable.

While there may be no specific regulation enacted by the state legislature or the local city council, there is a specific law that applies: the duty of reasonable care. If there needed to be a regulation for every conceivable situation, in order to hold someone accountable for their actions, our society would be buried in an unruly amount of regulations such as “thou shall not place razorblades on the walls” or “thou shall not use ice-skating rinks as floors.”

Violation of safety rules is evidence of dangerous conduct. Prudent people ordinarily exercise due regard for the safety for others. A “reasonably careful person” would not break the rules or act in an unsafe manner. A “reasonably careful person” would not act carelessly by violating safety rules because it could foreseeably hurt someone. All of these words and phrases are intrinsically tied together. To be negligent is to break the rules. It is as simple as that. There is no legal authority holding the words “safety rule” to be inadmissible under the Rules of Evidence or that such words are per se prejudicial. In essence, to ban “safety rules” is to preclude plaintiff’s counsel from using synonyms.

After all, “standard” is simply another word for “rule.” Black’s Law Dictionary defines “rule” as “generally, an established and authoritative standard or principle; a general norm mandating or guiding conduct or action in a given type of situation.” Likewise, the definition of “standard” is “a model accepted as correct by custom, consent, or authority. A criterion for measuring acceptability, quality, or accuracy.” With proper foundation an expert can testify regarding the scope of a duty even if it is called a “safety rule.”

Safety rules provide key evidence of foreseeability. Foreseeability of injury or danger is a key element of tort liability. Fundamentally, there must be a scope of duty before there can be a breach. “Foreseeability is used to limit the scope of the duty owed because tortfeasors are responsible only for the foreseeable consequences of their acts.” “It is for the jury to decide whether the general field of danger should have been anticipated.” “It is the jury’s function to decide the foreseeable range of danger.”

Safety rules provide evidence that one can reasonably anticipate harm caused by particular conduct, the foreseeable scope of the public exposed to the risk of harm, and the foreseeable severity of injuries that can be reasonably expected. In Wells v. City of Vancouver, 77 Wash. 2d 800 (1970), Washington’s Supreme Court explained that plaintiffs have the burden of demonstrating defendants violated a common “rule” to prove breach of reasonable care:

‘In terms of the elements of a cause of action for negligence, plaintiff’s counsel must be prepared to demonstrate that (1) there was a statutory or common-law rule which imposed a duty upon the defendant to refrain from the complained-of conduct and which was designed to protect the plaintiff against harm of the general type which he suffered, (2) the defendant’s conduct violated the rule, and (3) there was a sufficiently close actual causal connection between defendant’s conduct and actual damage suffered by plaintiff for the law to impose liability.’

It is not improper to advocate safety rules as a standard to be expected of all people in the relevant community. The wide latitude given to counsel includes argument to the jury to return a verdict that promotes the public policies of the law. “The concept of duty is a reflection of all those considerations of public policy which lead the law to conclude that a ‘plaintiff’s interests are entitled to legal protection.’” “One of the major purposes of tort law is to encourage people to act with reasonable care for the welfare of themselves and others… An underlying purpose of tort law is to provide for public safety through deterrence.” The “law of torts, as developed over the centuries, reflects certain basic social policies. These policies represent deep-rooted notions of fairness and justice in human relations…[and] evolved, in many ways, to embody the aspirations and ideals of a culture with respect to the relations of one man to another in the community.”

Over a century ago, the United States Supreme Court declared the “great principle that every community has a right to provide for the safety of its people… Salus populiest suprema lex [Let the safety of the people be the supreme law] is a maxim always true in all nations, and must be acted upon by all civilized, as well as all uncivilized, nations.” At the core of their societal purpose, trial lawyers across Washington serve as officers of the court, to safeguard their local community’s right to prudence and safety. The right to a jury remains inviolate, a role reserved only for the people, to determine the prudent standards most likely to effect safety and happiness, in such a manner as can only be judged by the community for the community, as the last and best place to safekeep our power to determine what is most conducive to the public interest under the circumstances.